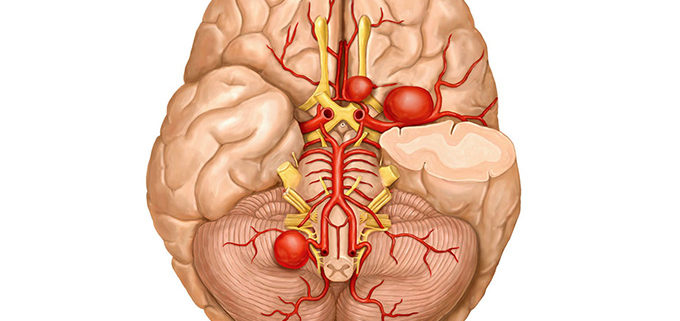

Rupture Rates for Small Brain Aneurysms

Growth and rupture rates in small unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) appeared to be relatively low, but the quality of published evidence is poor and current guidelines may need to consider specific follow-up imaging recommendations, researchers said.

A systematic literature review found that the annual growth rate for aneurysms 7 mm or smaller was less than 3% in all but one study, reported Ajay Malhotra, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

In 25 out of 26 studies, the annualized rupture rate for aneurysms 3 mm or smaller was 0%, less than 0.5% for aneurysms 3 to 5 mm, and less than 1% for aneurysms 5 to 7 mm, they wrote online in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Our review highlights that studies had substantial heterogeneity in imaging frequency and duration, as well as in growth and rupture rates of UIAs 7 mm and smaller,” they noted.

There was only one study with long-term follow-up, the authors stated with most studies having a mean follow-up of less than 5 years. The limited evidence indicates that “better literature is needed, including standardization of the definition of growth and the criteria used to treat small aneurysms.”

For patients treated without surgery or endovascular coiling, current 2015 guidelines from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommend a first follow-up study at 6 to 12 months after initial discovery, with annual or biannual follow-up. No specific recommendations are made for small UIAs.

“These guidelines may have to consider follow-up imaging recommendations specifically for small aneurysms (≤3 mm, ≤5 mm, and ≤7 mm), given their very low rupture rate and the poorly understood correlation between growth and rupture,” the authors suggested.

For the study, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library databases from inception to 2017 were searched for published case series and observational studies reporting natural history data on UIAs 7 mm and smaller. Out of 26 full-text articles, only 10 reported both growth and rupture rates, and many excluded patients considered to be at high risk for rupture.

Follow-up imaging methods (MRI, CT, and cerebral angiography) were inconsistent across all 26 studies. In 14 studies, follow-up didn’t account for patients with more than one aneurysm. Information on the frequency and duration of follow-up was insufficient to draw conclusions.

The results suggest that very small (≤3 mm) and small (3 to 5 mm) aneurysms have different growth and rupture rates. Since UIAs weren’t categorized by precise size in several studies, however, the authors were unable to divide them into mutually exclusive subgroups. Instead, they concluded that the rupture risk of aneurysms 5 to 7 mm was likely greater than that of UIAs 5 mm and smaller.

The risk factors for growth appeared to be consistent with those for rupture, according to the authors, noting that predictors of rupture risk in UIAs 5 mm and smaller may include initial aneurysm size, posterior circulation and anterior communicating artery location, and size ratio.

Small aneurysms may rupture infrequently but they can also cause subarachnoid hemorrhage, they pointed out. In 5- to 6-mm aneurysms, the rupture rate was 1.1% and aneurysms with a daughter sac that were located in the posterior or anterior communicating artery were more likely to rupture.

A study limitation was the high selection bias with regard to treatment of higher risk aneurysms in the reviewed research. Also the definition for growth varied between the reviewed studies.

In an accompanying editorial, Robert M. Starke, MD, from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, warned against concluding from this study “that small aneurysms have no risk for rupture but rather that experts are skilled at predicting which aneurysms are more likely to rupture.”

Although subarachnoid hemorrhage accounts for only a small percentage of strokes, its impact can be catastrophic, thanks to a “predilection for a relatively young population and the poor outcomes in these patients,” Starke pointed out. Almost 25% of potential life-years lost because of stroke are the result of subarachnoid hemorrhage, he noted.

Patients with aneurysms should undergo expert evaluation that includes a review of associated risk factors to “determine both the optimal follow-up plan (if any) and the need for treatment,” said Starke, noting that the mortality rate in patients with a ruptured aneurysm is about 50%.

This review “should prompt better prospective observational studies,” he stated.

Robert D. Brown Jr., MD, MPH, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., agreed. The risk of growth and/or rupture for smaller aneurysms may be low but it isn’t zero. Rupture risk prediction, and treatment recommendations should be individualized,” he said.

Brown, who was not involved in the study, noted that study provides a good summary of available data. He pointed out that aneurysm location and morphology are also important predictors of growth and rupture. Family history and selected risk factors such as smoking or hypertension may also be important predictors of aneurysm growth.

“These aneurysms are relatively commonly seen in clinical practice, often detected on brain imaging performed for other, unrelated reasons. The key question after the aneurysm is detected is whether the aneurysm requires interventional treatment, and if not, how should it best be followed,” he said.

Since it can be difficult to determine the stability of small aneurysms, follow-up with CT angiography and MR angiography “should be considered for unruptured aneurysms that are treated conservatively,” Brown said.

The issue of potential utility of medical management “is an important one,” he added, “given that there are some data to suggest that aspirin may be effective in lowering the risk of rupture. Management of high blood pressure and assistance with smoking cessation may be important too.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!